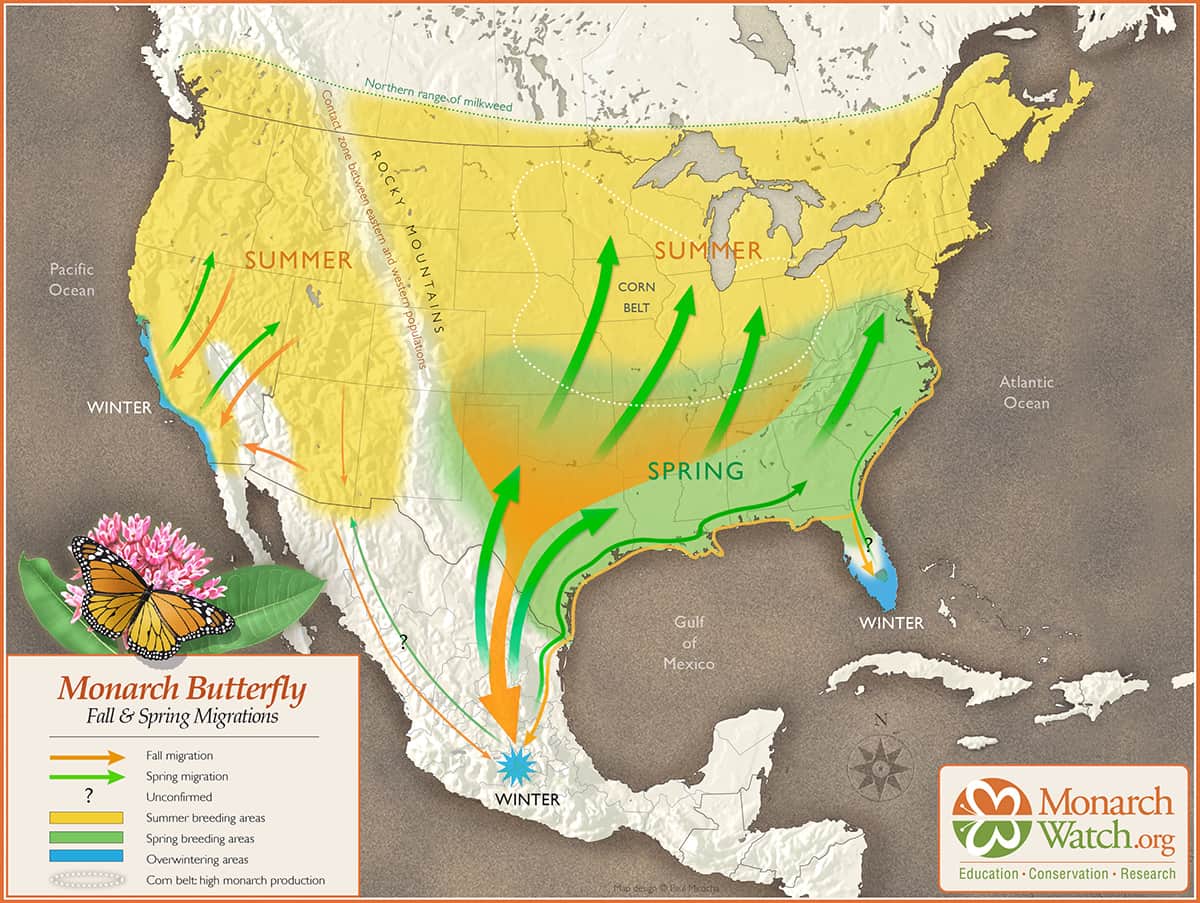

In North America, two monarch populations are separated by the Rocky Mountains. Western populations fly down the California coast. Eastern populations (our Missouri monarchs) overwinter in the oyamel fir forests of the Sierra Madre Mountains in Mexico. Monarchs are the only butterfly with such an advanced, two-way migration up to 3,000 miles long. Most other butterflies hibernate through the winter. Tropical butterflies migrate as well but are not as sophisticated or mysterious. The phenomena of the monarch migration has baffled scientists and is still widely studied – somehow, the monarchs know to return to the same trees their ancestors roosted in without ever visiting the forests previously. Because Missouri is in the path of the flyway for the entire monarch migration, this region is vital for maintaining the brilliant journey through conservation efforts.

Fall – southerly migration

Temperatures begin to drop, day length shortens, milkweed and nectar sources become sparse and the monarch realizes that it is time to head to Mexico. Most monarchs live four to six weeks, but those born at this time will have a different biological makeup that allows them to make such a strenuous migration. This “super generation” lives eight times longer and travels 10 times farther. To conserve energy, these monarchs biologically cannot mate or lay eggs. They also feast on nectar sources on the flight down in order to store fat for the winter ahead.

Winter – roosting in Mexico

Every winter, monarchs congregate in the Sierra Madre Mountains in Mexico. They roost at the same sites in oyamel fir trees. This area provides adequate shelter and temperature for the coming months. Before coming back to the states, monarchs biologically develop the ability to mate and reproduce. The “super generation” will start to fly northward, laying eggs along the way.

Spring – northerly migration

The “super generation” has started laying eggs and flying north. It will take around three to four generations to reach the northern United States. Missouri lies in this flyway migration pattern and is responsible for providing milkweed and other nectar-rich flowers for traveling adults. In the spring – usually early March – monarchs return to their breeding areas.

Summer – breeding and mating

Missouri and the entire Corn Belt region lies within the breeding grounds. After mating, females solely lay their eggs on milkweed species. These breeding regions host new generations, and eventually will host the new “super generation” that will migrate again in the fall. Without the proper milkweed and flowering habitat, the cycle and population is at risk.

Image courtesy of Monarch Watch.